“Osher at Carnegie Mellon University” lecture, delivered on August 6, 2020 The inspiration for this class came during a snack featuring peanuts and their crunchy shells. The result is a light – yet informative – overview of biomimicry and how it can help us creating better buildings.

Biomimicry (or Biomimetics) is a science that studies nature’s models and takes inspiration from it to solve human problems. Rather than merely copying how nature looks, the focus is on how nature solves problems. Since the dawn of the industrial Revolution, manufacturers have been building things by a process that is now known as “heat, beat, and treat.” The top biologists, engineers and scientists promoting biomimicry find fascinating how nature can do wonders at room temperature, with regular pressure, and by using only the energy of the sun.

The majority of people should be familiar with the concept of sustainability. Biomimicry is often associated with that term. Janine Benyus, a major advocate for biomimicry and author of the book: “Biomimicry. Innovation Inspired by Nature”, said that: “When we look at what is truly sustainable, the only real model that has worked over long periods of time is the natural world.” The claim is that the Earth has already done 3.8 billion years of R&D and it would be smart for us to look more carefully at what nature can teach us.

Biomimicry can generate solutions to many design challenges. It is also known as biomimetics and it is the design and production of materials, structures, processes, and systems that are modeled on biological entities and natural processes. We can look at nature at an organism level, a natural behavior level, or at an ecosystem level.

The most famous example of biomimicry is maybe the invention of velcro by George De Mestral in 1952. Before that, we can say that planes are somewhat based on how birds fly: Leonardo Da Vinci even tried to copy their wings quite literally. In architecture, many early civilizations (and their architects) have been fascinated by the golden proportion and fractal patterns, both in the Western and Eastern world. Frank Lloyd Wright was the most famous promoter of the organic architecture. Antoni Gaudi was also a supreme master of the organic, even saying that the straight line belonged to men and the curved line to God.

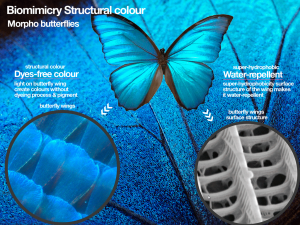

In the recent years, biomimicry in architecture has often meant progress in materials science: Bio-engineering teams are developing biomimetic technologies like the self-healing concrete, biologic bricks mimicking how shells harden, bio-inspired pavilions mimicking the skull of crows, or shading devices that resemble leaves and create different shading at different temperatures.

Scientists like Neri Oxman at MIT are pushing the limits of 3D printing organic matter like chitin, naturally present in crabs. She also uses silk worms as a living 3D printing machine, as she explores what she calls “material ecology”.

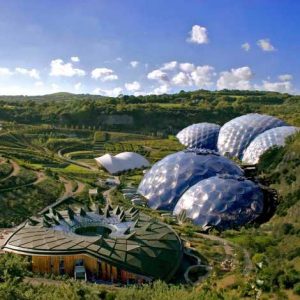

At a building level, a great example of biomimicry in architecture is the Eden Project, in Cornwall, UK. The domes contain the largest indoor rainforest and feature an hexagonal structure. Such a structure makes it possible to us less material (steel) and mimics bees nests, but also bubbles. Hexagons are the best (natural) way to create spherical structures, which are able to cover uneven terrain efficiently. Another example is the Biomimetic Office, designed (and not yet built) by Exploration Architecture and Michael Pawlyn – an institution in the field of biomimicry applied to architecture. This office optimizes the walls and the roof so that a lot of natural light can come in. They were inspired by a spook fish and the structure of its eyes that, even at low light conditions, can capture light.

Going maybe even beyond biomimicry, and entering in the realm of scientific and artistic installations, we have to mention the work of Philip Beesley, trying to mimic a “natural metabolism” in his delicate and fascinating works and considering his work as “living architecture”. We also want to talk about Jenny Sabin and her ADA project, in collaboration with Microsoft. The goal of this installation is to mimic how humans react to facial expressions and body language. As Janine Sabin said: This sculpture literally smiles back at you.

For anybody interested in the field of biomimicry at large, the go-to resource is the Biomimicry 3.8 Institute. They have developed the Design Lenses tool with the goal to help anybody willing to pose a challenge to biology, or just working the other way around, from biology to design. Thanks to their Design Lenses tool – and a basic digital microscope – I have developed some ideas too and presented them during class. After extensive research on existing papers and with the aid of original drawings created by me, I presented the biomimetic process for:

- A bamboo-inspired tower with extraordinary slenderness ratio

- A shading device that requires only one attachment and is inspired by bees wings

- A material that feature structure and insulation in one module, inspired by peanuts

- A model of a more sustainable (and even equitable!) city, based on how tropical forests work.

If you want to learn more about the research that has been made to date – and the references for this class – you can read the full text of the lecture. If you have questions on the content or if you are interested in us delivering the class for your organization, you can contact Bea at bea@fisherarch.com