Thanks to all who joined two of Pittsburgh’s top architects, Eric Fisher and Art Lubetz, online at Osher CMU Thursday, October 28 and Thursday, November 4. Our topic, which we discussed in front of an audience of eighty or so virtual guests, was “design excellence”.

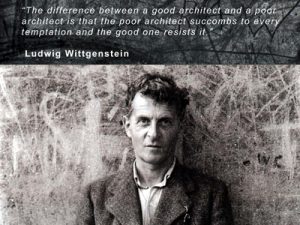

Everyone believes that architecture should be “good”. Yet what does that phrase even mean these days? The profession is in a poor place despite the rare exceptional new building that proves the rule. Architects design just two percent of all American houses these days. And all around Pittsburgh, mediocre new buildings that ARE designed by architects have come to blight our urban landscape. How can that be considering that there are now so many rules for determining what constitutes design excellence?

Near the end of the first century B.C.E., the Roman architect, Vitruvius, suggested that buildings should exhibit “Firmness, Commodity, and Delight.” In these talks, the speakers will define what makes a building great TODAY. They will address the questions, “What values should contemporary architects bring to the table as they design?” and “What qualities should these buildings possess?”

Here is what I had to say on Day 1 of our two part endeavor:

Part 1: Design Excellence (WEEK 1)

So what is design excellence?

For me, Art, it’s not about the way the projects look: Excellence is more of an ATTITUDE that we aspire to.

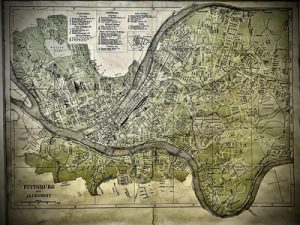

How can I say this considering the unfortunate look of so many of Pittsburgh’s new architecture. One after another, ugly new buildings have sprung up all around our beautiful city until it seems we can’t walk more than a block before we come onto one.

To answer, I would suggest the following: The way the buildings look IS important. I’ve staked my whole career on creating a style of architecture that I believe a) reflects and reinforces the character of Pittsburgh, while b) connecting to buildings that are being constructed around the world.

Yet, I’m not so sure of myself to say that what I believe is right and what everybody else believes is wrong. Certainly I have my opinions, and you will hear them – that’s why members of this class signed up – yet other thoughtful architects certainly also have strong ideas.

Meaning

Times have changed. The qualities that would have allowed an architect to succeed back in the day have changed: In the past the architect/creator was thought to determine the meaning of his own buildings. When I was in school, designing buildings was considered to be a bit like cultivating plants: An architect would plant the seed of an idea on paper – often based on the precedent of other buildings that shared similar programmatic or spatial inclinations – and the design would sprout organically in response to his vision. There was only one best way to proceed through this process.

An architect was like a very active gardener, nurturing and shaping the project to its end result, which was thought to have qualities of the absolute. The architect was the “determiner” of the building’s meaning. He was the guy in charge of bringing the building to a singular, quasi-objective place where human knowledge was restricted.

I worked for the skilled architect, Richard Meier, for five years as one of twenty architects on the magnificent Getty Center in Los Angeles. It was a truly impressive project in many ways. But Richard was an architect who was an old-school absolutist. He used the same ideas over and over again. Every building he designed was an immaculately crafted combination of simple white shapes that were tautly aligned with rigorous three-dimensional spatial grid systems. Why would he do this? If you had asked him and he had answered truthfully, I believe he would have said it was because there was only one right way to design buildings. HIS way.

There is no one right way to design

Yet our generation, and those that have followed, are no longer as certain of ourselves in any of the arts – literature, film, painting, sculpture, you name it – as were those who preceded us. In 1995, Ellis School graduate, Annie Dillard, was writing personal memoirs at the same time Toni Morrison was writing one of her own. Both are hugely skilled writers but they couldn’t be more different in their approach. The archetype of the genius creator, almost always a white male, has been dispelled. MEANING in architecture is now thought to not be determined by the architect’s intent, but rather from the cumulative experiences of ALL of a building’s users. And there are as many potential users of a building, each with their own inclinations and background, as there are people in the world.

This is liberating for architects because there is no longer one right way to design. Now, our buildings are free to change in appearance based on the conditions of their making. It used to be that certain combinations of forms were thought to be imbued with character and truth.

Now, architects get to invent the truth as they go along.

Some architects may express traditional historical styles more directly than I. Others may value involving the community more during their process. (They may see design as a collaborative effort that requires the buy-in of many points of view.) Still others may focus on parametric design, or the quality of the urban environment, or sustainability, or color, or the relationship of building shapes one to another, or any number of different elements.

One thing is for sure though. They will all design differently than I do and that’s OK. Now we don’t get to be right. We just have to be good!

The Challenge

That thought has had enormous consequences for me. I am now secure in the knowledge that I don’t have to be a genius to design excellent work and contribute in a meaningful way to our profession. I don’t have to have, say, the 3D visualization ability of Frank Lloyd Wright or the political skills of Philip Johnson. And I don’t have to design at the huge scale that Starchitects design at either. Projects of ANY size can now contain meaning.

So that’s why attitude matters. We architects may not be so sure about things as we used to be but we CAN create conditions so that excellence is at least possible. And then let the chips fall where they may as people have their say…

My opinion is that the way most architecture firms are designed don’t allow architects to excel. But with the right attitude, I feel architects can still design meaningful work. In my remaining time today, I will address the problems that our profession faces, and ways that architects can address these difficulties.

Technology:

Technology presents huge challenges. It is true that new architectural computer applications have done great things for architecture. Certain architects are designing – and getting built – buildings with configurations that couldn’t even have been imagined just fifty years ago. And many of the new technologies we are using, like Revit for example, can double the speed of an architect’s process. But they do so at a cost. Revit in particular encourages the use of generic system “families” that dumb down a building’s details.

It’s not just our means of production that are affected by technology. These days, architects are mostly handling their own communications. If you were to call me tomorrow, I would likely answer the phone myself. That’s a good thing for sure, especially if you are my client. But still, It takes me hours every morning just to go through all my telephone, email, and text messages. I didn’t realize the extent to which this time was subtracting from the time I had to design until I travelled to Italy this summer and practiced from there for two months. I found myself truly relieved to be out-of-touch with folks in America until they woke up at what was, by then, 2:00PM in the Alps.

Slowing Down:

What sort of attitude will permit architects to use technology without being controlled by it?

I believe that architects must be compelled by their nature to design: They MUST schedule their days so they actually have the time it takes to create strong work.

They…MUST…take…their…time. Slow down, I tell my interns all the time. Think about what you are drawing and you’ll do better work.

Second, while architects must always embrace change – because the world will go on changing whether architects do so or not – they MUST feel compelled to practice and maintain ALL their skills, not just those that lend themselves to production. Not to sound like an old fuddy-duddy, but no one can sketch anymore. The connection between the brain, the hand, and a piece of paper is special. Pushing buttons and moving a mouse simply can’t match it.

I urge my fellow designers to paint that watercolor, to scribble that sketch for the client, and to turn off your social media, if only for a time, so that you can concentrate more fully on what we truly do for a living. WE are the ones who are responsible for creating the urban landscape of tomorrow. And no one else is better educated to do it better than we are.

Money:

Money is always short at an architecture studio. Certain psychologists have suggested the self-obvious truth that it’s difficult to empathize with others while you are starving. For children, it makes sense that the development of a caring attitude requires a full stomach. Most architects, certainly, are not starving, but their business models require them to churn projects in order to stay in business. You’ve got to feed the beast. And this discourages thoughtfulness. If a solution has worked once for most architects, then it gets reused in order to preserve the architect’s all-important cash flow.

My thought is that architects should NOT be businesspeople FIRST. My personal experience confirms that money will follow if you put quality first. Architects should be determined to do excellent work.

This opinion would make many practicing architects roll their eyes. Here they are trying to feed themselves and their families, working ungodly hours to pay off their massive student loans, and some guy comes in and tries to tell them how to run their lives. To these folks I apologize. I get it. I really do…

But to young people who are considering architecture I say the following: There is no point in becoming an architect unless you intend to be really good. It simply takes too much time to get educated and registered, and you can make more money in many, many other professions. I tell people all the time that “You become what you do.” If you don’t design quality work, then you won’t become a quality architect. Go to the best school you can get into. Work for the best people you can. And if you start your own firm, then aspire to be the best. Because otherwise it’s simply not not worth it.

Firm Structure:

The way most commercial firms work, the majority of the work gets designed by just-registered architects and designers. Experienced architects are channeled into marketing, development, and project management. So the quality of the resulting design suffers.

And that’s not the only problem with this model: The just-registered folk doing the actual design are learning the poor lesson that this is the way design works. When I was a Project Manager for a strongly regarded Los Angeles corporate firm, I was the architect of four projects at once because the perception was I could draw quickly. That was not good for the design, and it wasn’t so great for me either…

My first thought is that younger architects should learn about design from watching their older peers at work.

My second thought is that architects MUST continue to design throughout their career because the more they design the better they get. It shouldn’t be enough to guide someone else’s pencil. I would hope that architects would be compelled to create things themselves throughout their careers. Experience matters after all. There is a reason why our career is called a “practice”.

Design:

Architects most often tend to design buildings that can be constructed as cheaply as possible, with super-inexpensive materials and technology. In the end, say many of my peers, people want a roof over their head in a heated place where they can live or work or sleep and nothing more. Space, I have heard reported more than once, is more important to most people than quality. So buildings get dumbed down to account for the architect’s perception that clients are not open-minded.

But that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: As the 19th century thinker, William James, once wrote, “It is our attitude at the beginning of a difficult task which more than anything will affect a successful outcome.” How can architects know what their clients will like if they don’t challenge their belief systems?

Challenge your Preconceptions

I humbly suggest that architects MUST continuously challenge their own preconceptions. To quote the artist, Jenny Holzer, I say “Please Change Beliefs”.

When I was a crew coach back in the day I would tell my rowers to “Go Gumby”. By that I meant they should relax their shoulders even as they were pulling within an inch of their lives. To be an effective rower you have to stay relaxed and flexible even as lactic acid is flooding your arms and legs.

It’s really tough to do.

And so it is with professional life. Architects are often faced with unfamiliar situations that require new solutions. Many get pulled in one direction and go with it. But architects can only learn and grow if they are willing to question the ideas that got them where they are.

One great way to challenge your beliefs is with education. Here I’m preaching to the choir! Architects MUST continue to learn new skills, not only in order to compete with other architects or to gain clients, but because learning is really, really good for you.

Be open to what the universe brings you, and although you may not be rewarded financially, at least you will be smarter…

Clients:

Clients are great but sometimes they aren’t: This one is an architectural variant of the “Monkey’s Paw”, perfect for Halloween: Many clients really don’t understand quality and truly aren’t open to new solutions. Pittsburgh is a conservative city. Without education, and without examples of good design readily available, clients often don’t know better. Developers especially often succumb to this disease. They know what has worked for them in the past and often aren’t willing to take what they suppose to be risks.

In the end, clients are the boss so they get just what they want. That horrid thing knocking on the door at midnight is often the ghost of the Pittsburgh developer’s old projects!

Architects MUST be willing to educate others even as they are educating themselves. If we don’t communicate our ideas honestly, and take every opportunity to persuade our clients to our point of view, then we are doing neither them nor us any favors.

I also recommend that architects teach in order to spread the word. And they should lecture when they get the chance. They will likely find that even as they are educating others, they will be educating themselves.

Contractors:

Many contractors simply can’t build custom. A few I’ve worked with can barely read drawings, much less decode details. So asking them to build something with unfamiliar techniques is an exercise in frustration. This problem is amplified because, more and more, architects are not involved with what is called “construction administration”: Especially if the architect is being paid hourly, he will not get invited often to the site to assist in solving problems because the owner knows it will cost him. And the contractor is often just as happy to make up his own solutions that may or may not have any connection to the architect’s intent.

Craftsmen:

It’s not just the contractor who is at fault here. The labor forceis much less skilled: There used to be a community of craftsmen in the United States who could build just about anything an architect could design. That community is no longer. Even in Japan, a nation that loves detail, far fewer young people choose to become skilled tradesmen, or “shokunin”, as their countrymen all them. And in Italy, the Vatican reported this summer it can no longer find artisans to produce and restore religious articles.

So it is in Pittsburgh: Check out the incredible detail in Henry Hornbostel’s Shadyside Rodef Shalom temple. You simply couldn’t find people to construct that structure today. That level of built-in quality used to assure that every building, not just those that were special, would have a certain amount of visual interest. Today architects can not design the things they used to.

But architects must NOT become cynical or bitter. The world is always falling apart and it is ALWAYS born anew. The conditions I mention above ARE real. But things have always been tough for designers, and most buildings have always not been great. Old detailing techniques may not work anymore but new ones have come to take their place. And some Pittsburgh contractors can still exhibit true excellence, especially when given the right client and the right project

Part 1: Conclusion

In conclusion, here is what it takes for an architect to create excellent work:

- Architects must not become cynical or bitter.

- Architects must take risks.

- Architects must love what they do.

- Architects should not be businesspeople first.

- Architects must be educators.

- Architects must educate themselves.

- Architects must design throughout their careers

- Architects must take their time.

- Architects must continuously challenge their preconceptions.

- Architects must work in teams but they must be individualists with a point of view. (I didn’t talk about this one…)

You don’t have to be perfect. It’s like a successful marriage: You just keep trying to do the best you can. By trying to accomplish all these goals, architects can maintain the most important quality that it takes to design excellent buildings: They can continue to love what they do.

Maintaining a love of good design is important because, when all is said and done, you can’t force yourself to become someone you are not. Rather you have to want to become that person: You have to feel that the things you are doing have a deeper reason and a purpose or you won’t be able to sustain the energy and effort that it takes to accomplish excellent work.