Artist of the Year: After more than 40 years, Eric went back to his high school and presented in front of the assembled student body at the Haverford School. It was exciting for him to see how the school has changed and to learn that the program was so well organized:

He was truly inspired by the maker spaces and art classrooms. Eric felt grateful and honored that Chris Fox, the Art Department Chair, had invited him to be featured as “Artist of the Year“! Here is a link to the text of Eric’s conversation with Haverford Marketing and Communications Director, Sarah Garling. Below is the text of his presentation to the school.

Introduction

Hi folks, I’m happy to be here. It’s exciting to be back on campus for the first time in – can it be – forty four years. That’s an astonishing amount of time. Yet it seems like I was here just yesterday. “A blink of an eye”. It’s a cliché but one day you’ll say the same.

You may be wondering what the school was like back then. The facilities have been updated – the place looks great – but I think it’s probable that the school experience is not too different for students now than it was at that time.

Highschool Memories

So maybe you can relate when I tell you I sometimes felt like the biggest nerd at the School. I was on the smaller side – I remember wrestling varsity at ninety-eight pounds my freshman year – but I found a great group of friends and that helped me a lot. As I look backward, I am astounded at how inarticulate I was. Yet somehow I survived and got into Dartmouth College off the waitlist. I thank Haverford for that.

Walking through the front gate and up the steps into the building really brings back memories. Here’s one: My family lived nearby so most days I would walk to school. One morning, I remember walking across Montgomery Avenue one morning my freshman year. I must have been super-tired and lost in my thoughts because I stepped out into the street without looking where I was going and got nailed pretty hard by a mid-size car. I was able to put my shoulder down in time and my bookbag took most of the impact. My books went flying but by some miracle I was OK. I was pretty shook up. But that afternoon I won my first varsity wrestling match after having lost my first five. I’ll never forget that.

Reading Saved Me

I think there’s a lesson there: My books saved me that day. That was the first time they would do that but it would not be the last. All that reading I did as a kid really taught me to think. The heroes of the books I liked the most taught me that standing up for what you believe is a good thing. They taught me that thinking out of the box is OK. They taught me that there was an interesting, terrifying world out there that was radically different from the sheltered country club existence I’d experienced as a kid. And they gave me some assurance that at some later point in my life things were going to be MUCH better for me than they seemed at the time. In short, they gave me a good dose of much-needed context.

Here’s another thing I learned from books: I didn’t have to become a stockbroker like my Dad if I didn’t want to. There was a whole world of professions out there. I could do anything I wanted!

“Your Own Track”

So as Chris told you, I’m an architect. As I look back, it is clear that the route to where I am now didn’t follow a “normal” path. But what does normal even mean? I was fortunate to study under the great Spanish architect, Raphael Moneo, when I was in grad school. Desperate for assurance that the housing project I was designing in his studio wasn’t a train wreck, I once asked him if I was on the right track. “You are not on the right track”, he replied. “You are on your own track”.

I get it: Just as there is no one right way to design a project, there is no one right way to lead your life. We are all on our own track. Being normal is overrated.

As I mentioned, I attended Dartmouth after graduating from Haverford. There I double majored in engineering and art. Also, I became president of the dormitory student government and developed a deep love for the outdoors. I grew up a lot. Every day it seemed I was hiking or skiing or running in the hills near the college, which is located in New Hampshire next to the Connecticut River in a tiny town called Hanover.

Alaska

As a senior I had a thousand or so dollars saved up so I decided to see the world. It took less money back then to travel than it does now… So starting in Hanover, armed with travelers’ checks as there were no ATM cards at the time, I bicycled across the United States to Washington and then to the end of Vancouver Island in Canada. From there I hopped a ferry north to Ketchikan, Alaska where I got a job at a cannery gutting fish with the seasonal workers.

Thirty days later I used my engineering degree to land a job with the Forest Service as a surveyor. For six months I lived on a boat on Prince of Wales Island just west of Ketchikan. Our team flew into the nearby mountains every day by helicopter. We’d spend our days hiking through the woods and our evenings fishing for salmon.

It was a rough crowd – a guy arrived back from town one Sunday evening with a nasty knife wound from a bar fight. Another would shoot salmon out of the water from our boat with the gun we would use in case the bears got too aggressive. Yet for the most part I was able to get along and enjoy my life there, even if my background was very different from that of those around me.

Graduation!

Then I returned to Dartmouth, graduated, and flew back to Ketchikan where I worked for a year as a Civil Engineering tech. At the time I thought I would become an engineer, but part of me had always wanted to be an architect. After a year of work I had made up my mind: Using the photographs I’d taken on my travels as a portfolio, I applied to grad school at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. I figured if I could get into the best school in the world it would be a sign – to myself and to my parents – that I was making the right decision.

Architecture

My parents weren’t fans of me becoming an architect. My Dad especially was worried I wouldn’t be able to make a comfortable living. I’ll say this for my Dad though: Later, when he saw I was going to be successful, he became my biggest fan.

I made it through Harvard, though it was often intimidating to be surrounded by such a talented group. It seemed I was always playing catch-up. Following graduation I worked in Berlin for six months. Then I lived in Boston for five years before moving to Los Angeles, where I worked fifteen years for three of the world’s best architects, Larry Scarpa, Richard Meier, and Frederick Fisher (no relation).

When I had lived in Cambridge, I had fallen in love with rowing, a sport I would practice for the next twenty years. Every morning when I lived in LA, I would get up at 4:30 and bike or drive to Marina Del Rey from my Hollywood apartment to row with my teammates before heading off to work. For two years while I was helping to design the Getty Museum for Richard Meier, I was even the varsity crew coach at Pepperdine University!

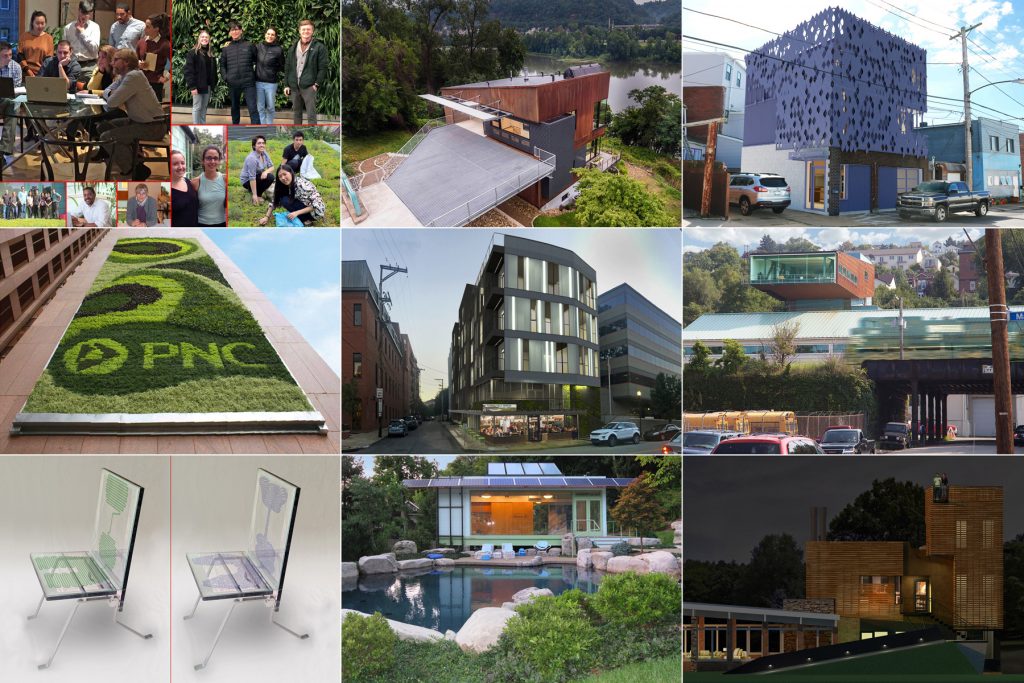

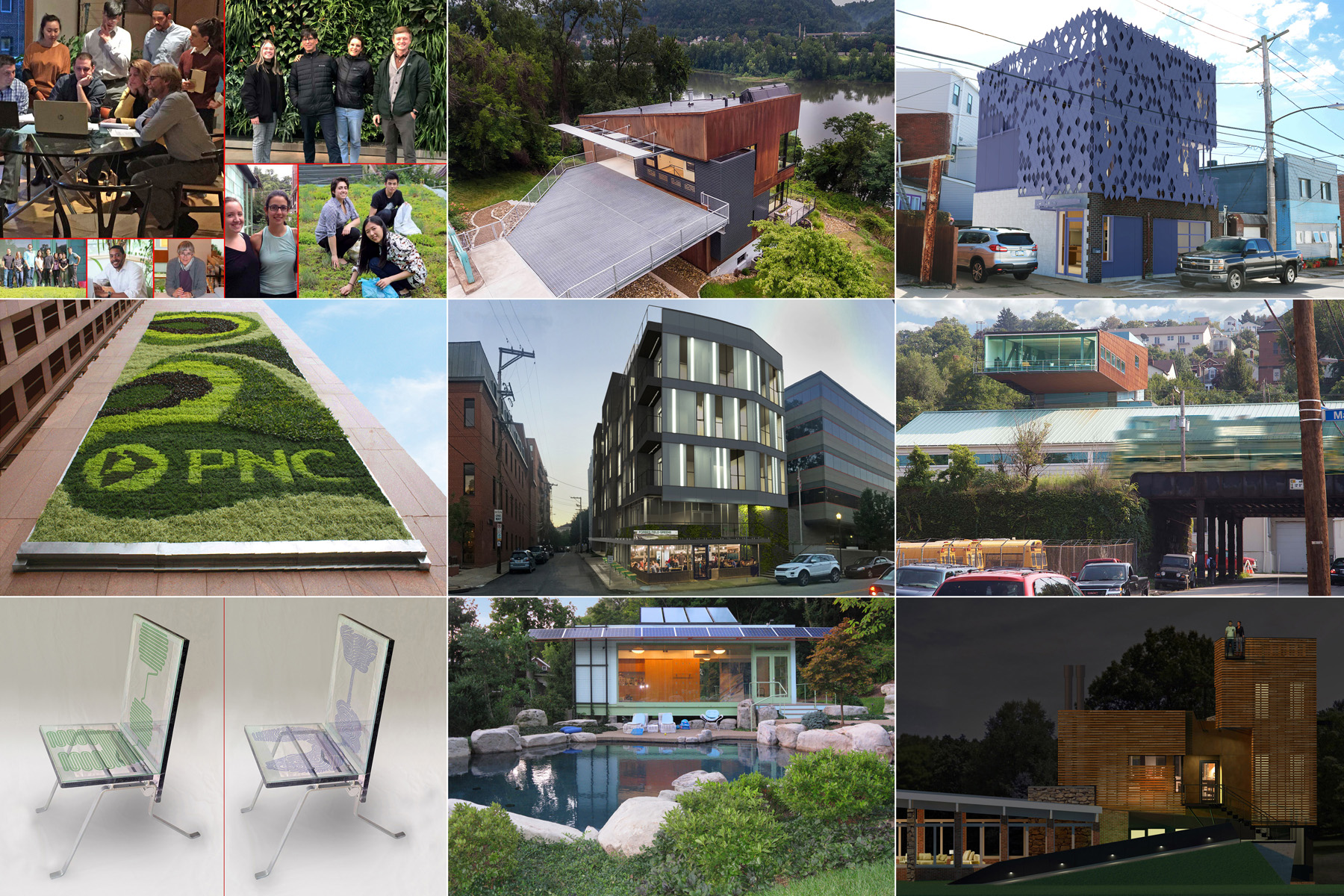

By then I felt I knew enough to have my own business. And my parents, who both lived in Pennsylvania, were becoming older so I wanted to live closer to them. Armed with an offer from a strong Pittsburgh architecture firm and a teaching offer from CMU I felt comfortable moving back East. Two years later I started my own business, Fisher ARCHitecture, just as the bottom fell out of the housing market.

Fisher ARCHitecture

When I started Fisher ARCHitecture I had the mistaken preconception that because I had graduated from a good school and had good experience that people would necessarily want to work with me. To put it simply, I opened my firm and waited for the phone to ring. In case you were wondering, it doesn’t work that way…

Yet somehow I was able to get enough work to pay my rent. I learned to run a business as I went along. I designed and built my own home, which was published nationally.

Also, I was fortunate early on to get a job with an adventurous couple to design an extraordinary home on the edge of a cliff. The biggest lesson I learned early on was that in order to be a successful entrepreneur, you really have to put yourself out there.

Not only was I not a natural extrovert, I had been taught by my parents not to show off too much. It was a tough time. But, as I used to tell my rowers, “You have to feel comfortable feeling uncomfortable.” When you are a rower you have to relax your shoulders even as your body is flooded with lactic acid. So I sucked it up and acquired skills.

For fifteen years now I’ve been running Fisher ARCHitecture. I met Bea a decade ago and was smart enough to marry her. Three years ago she joined me as a principal at my firm. We’ve had a great time working together. Our lives are filled with adventure and we love our work.

What do Architects Do?

What do architects do? Well put simply, we design buildings. But of course things are never as simple as they appear. We architects have to wear a lot of hats:

We get to be communicators and mentors: I speak at a lot of events and I’ve been a professor of architecture in every city where I’ve practiced. I write a lot too, mostly but not always about architecture.

We get to be techies: There’s a fair amount of math and science related stuff involved in what we do. There’s a lot of software to master, and a lot of information you have to know: environmental stuff like the LEED standard or Passive House, structural stuff, code stuff, and even programming stuff: Just this year I taught myself Grasshopper which is a parametric plugin to Rhino, my primary 3D design program. You can Google “parametric architecture” if you want to learn more. The results can be wild!

We get to be entrepreneurs: I write a lot of emails, I have to bill my clients, run an office, coordinate marketing and business development, and attend a lot of meetings.

We get to be artists. I draw every day, sometimes with paper and pencil and sometimes on the computer. As my wife, Bea, will attest, I spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about how my buildings will look and how they will feel when folks walk through them. That’s the fun part for me. Even as I was writing this talk I was designing and rendering a project on my second computer.

Being a Poet

On a really good day, we get to be poets. Yes, when you graduate from high school, being a poet is a good thing… As Louis Kahn once said, “A great building must begin with the immeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed, and in the end must be unmeasured.” And Frank Lloyd Wright wrote that architects were poets because they must be great original interpreters of their time, their day, and their age.

And we get to be students. Don’t think for a moment that you stop learning when you leave school. Every day I’m learning new things. It takes a lot of time to soak in everything you need to know in architecture: It’s no accident that the famous architect, Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t design the Guggenheim Museum till he was in his nineties.

Living a Full Life

Architecture is not the only subject I’m studying: My wife, Bea, is from Milan, in Italy, and I’d like to be able to speak to her parents in their own language. Also, we’re planning to live in Italy one day. So for the last three years I’ve been learning Italian. – “Buon giorno, Sono felice di essere qui!” The prepositions are tough!

This summer Bea and I will be bringing our work to the Italian alps and plugging in near the Swiss border for two months. We did the same last year.

Then before we came home we bicycled for two weeks on an old Roman road from Luca into Rome. This year we plan to spend our two weeks biking through Greece. Not all bad!

Why Architecture?

I looked this up the other day. Check out these numbers: According to Harvard’s daily newspaper, fully three quarters of all Harvard grads are going into finance, consulting, or technology while only three percent plan to pursue the arts or education.

I have a warning for all these talented folk: No one remembers Shakespeare’s banker.

Writers, artists, musicians, architects, other creative people. THESE are the folks who will be remembered: Back in the day, my Mom used to be head of development at the Ellis School, a private girls’ school in Pittsburgh. The school has attracted more future applicants as a result of the success of ONE graduate, the super-talented writer Annie Dillard, than they have from all of their other graduates combined.

We make our decisions as we will and then the results of those decisions form us in return. Like rowers, we advance looking backwards. Examining our past, we come to believe that our actions have had a reason and a purpose, and that they have had meaning. And that informs our future decisions.

You’ve Got to Take Risks to Succeed

As I always tell my students, you become what you do: As Mark Twain once said, “If your environment is not making you better, change it… Loyalty to petrified opinion never yet broke a chain or freed a human soul.”

By taking risks I’ve come to believe that risk-taking can pay off. By advocating for my version of quality, I’ve come to believe that quality really matters.

And by talking about architecture for as long as I have, I’ve come to believe that architecture is important. Every profession is a sort of frame that organizes and directs your life. It points you in a direction. It provides you with certain opportunities while limiting others. I believe I could have been content as an engineer or even as an accountant, but I’m really happy doing what I’m doing. And I feel good about the person I’ve become.

To be clear, in case you were wondering, most architects make a good living. You can look it up. And what we do is objectively important: Architects are the ones who are responsible for creating the urban landscape of tomorrow. Bea and I have a super-nice home and can travel when we want. Sure we work a lot but that’s OK because we love what we do. Being an architect is not easy: It can be a humbling profession because there’s so much you need to know. But it can also be a lot of fun. It’s certainly never boring.

To this day, Bea and I believe our best projects are ahead of us. In our hearts we believe we’re only just getting started!