In February, 2018, Louise Sturgess, Executive Director of the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation (PHLF), invited Eric to present his ideas about “The Future of Pittsburgh Architecture” to two groups of Pittsburgh Realtors. PHLF’s continuing support makes it clear that they share our idea that it is possible to design progressive buildings while still honoring and preserving our city’s rich architectural past.

Into the Twenty-first Century?

Today we will lay out the forces defining contemporary designs around the world. Then we will turn to Pittsburgh and define a couple of factors that makes our city unique. Then we will make a couple modest predictions regarding the future…

Streams of Global Architectural Design

Here are the three defining streams of thought contributing ideas to contemporary architects:

1) Contextualism

Buildings that are contextual connect in various natural ways to their surroundings and to the conditions of their making.1 Today’s contemporary designers who are aware of theory often identify with a contemporary movement in architecture called Critical Regionalism. “Critical regionalists seek to provide an architecture rooted in the modern tradition, but tied to geographical and cultural context.”

The word architects often us to describe as a metaphor for this phenomenon is “palimpsest”, which is a parchment on which partially visible previously written layers are still visible. Palimpsests are super-interesting because they not only communicate two dimensional information, they also communicate information in the third dimension of time, by communicating information from the past.

So when new structures will be built in the city or old structures are adapted to new uses, it is preferable now that architects carefully reinterpret history so that the structures respond contextually to their locations. The goal is to create new post-industrial landscapes that are rich with memories and experience. Similar to the Italian architect, Aldo Rossi, architects are now saying that, “The city itself is the collective memory of its people, and like memory is associated with objects and places.”

This doesn’t mean that new buildings simply copy the look of adjacent older buildings. “It is a progressive approach to design that seeks to mediate between the global and the local..”2 Our idea at Fisher ARCHitecture is to let old be old and new be new. Treat existing buildings with repect: Restore them and preserve them whenever possible. But when you build new, build in such a manner that you respond to today’s needs and construction techniques.

McCullough Mulvin’s architecture provides good examples of this trend. Their buildings have been described as mneumonic devices. What is a mneumonic device? It is a technique a person can use to help them improve their ability to remember something. It can be a song, or a rhyme, or a phrase. One example I remember is “Every Good Boy Does Fine”, which are the notes on the lines of the treble clef. Buildings can be mneumonic devices if they bring to mind preexisting project conditions.

At their best, contextually driven designs can provide windows to the past. They can communicate information to users that would otherwise be lost. And they can respond in unexpected ways to site conditions, providing unique experiences for users, establishing what urban designers call “a sense of place.”

2) Neomodernism and Minimalism

The language of forms almost all young designers are now using is that of Modernism. The most obvious example of an architect inspired by Modernist ideals is Richard Meier. He came of age just as the first wave of Modernism was ending in the 1960s. Richard Meier lived and learned through the postmodern seventies but kept returning to a conceptually and formally pure language of white forms. He was an admirer of the great French architect, Le Corbusier, who first developed his “Five Points of a New Architecture” almost a century ago in 1923. These five points were non-load bearing columns, a free plan, free facades, horizontal windows, and roof gardens.

Most often this sort of architecture is “reductive”. The concept of minimalist architecture is to strip everything down to its essential quality and achieve simplicity. Minimalist buildings are reduced to a stage where the architect can not remove anything further to improve the design. This movement has it’s strengths and its weaknesses: It was the Modern architect, Mies van der Rohe, who coined the phrase, “Less is More” and the Postmodern architect, Robert Venturi, who responded that, “Less is a Bore.”

3) Neoexpressionism

“Neoexpressionist” architecture is architecture that, in contrast to Neomodernist examples, exhibits novel materials, formal innovation, and unusual massing. This kind of architecture is meant to provoke an emotional, not an intellectual response3 One architect who has designed in this way is Zaha Hadid. She was influenced from the beginning of her career by the artist Kazimir Malevich, who led her to use paint as an exploration tool.4

Here in the US, architects interested in expression are often inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and his talented students, Rudolf Schindler and John Lautner. I found myself moved as well by these architects’ timeless designs. But Wright’s Falling Water was designed eighty three years ago, and Schindler’s Kings Road residence was designed almost a hundred years ago!

The architects of these novel buildings are different from one another in many ways but they have one thing in common. While on the one hand they are progressive, on the other their work is firmly tied to the history of architecture. Each of them is tied directly to a current strain of contemporary architectural thought that has its roots in the past. Inevitably, their buildings clearly express the conditions of today’s place and time. Fifty years from now folks will look back at copies of those great architects’ buildings and say, “Oh yeah, that was from 2020.”

How is Pittsburgh Unique?

1) National Influence

Pittsburgh is a great city. It’s a very strong regional center. But I can say with a fair degree of certainty after visiting Chicago, New York, Milan, and Barcelona in the last year that our city is not an international hub. That’s part of the charm.

How does this affect us? There’s an old joke that I found reprinted on the Cranberry township business hub webpage as I was doing my research for this talk: Because Pittsburgh always seems to be ten years behind the rest of the country, if someone were to announce that the world was coming to an end, people would flock here so they could stick around for another decade. I looked up the joke because it was so good and found that over the centuries it has been variously applied to Cincinnati, Hartford, Bavaria, Dresden, and the country of Holland.5

And so it is with our city’s architecture. We’re ten years behind. So if you want to see where Pittsburgh will be in a decade, look to New York, LA, and maybe Milan and Berlin, because we design in a global design community. We are affected by national forces. That’s a good thing, because by looking to the larger cities around us, we can see what is working and what isn’t.

2) Building New Versus Renovating

While home listings have dropped dramatically across the nation over the past five years, making it harder for prospective buyers to find a house, Pittsburgh has actually seen a slight increase. People looking to buy a home in Pittsburgh should have an easier time than people in other major metropolitan areas, such as Portland or Charlotte.6 That means, – need I say it! – that sellers here won’t get as many good offers as in other places. Result: This has been keeping real estate prices relatively low here in Pittsburgh.

Renovations: These low prices mean that at this time developers and owners are less likely to build from scratch here than in other places. As their profit margins are less secure. If it will cost you $150/sf to gut a four unit apartment building and fix it up, or it will cost you $200.00/sf min to tear it down and start again from scratch, you are far more likely to choose the renovation route here considering that the price you can sell at is lower than it would be elsewhere. For a minute forget about the cradle-to-grave-resource-usage argument for a moment or the old-buildings-communicate our-city’s-history argument. My opinion is we’re mostly saving old buildings because it is cheaper to so.

To be clear that is not always the case with larger projects. When I first moved to Pittsburgh, my first boss here in town, Leonard Perfido, hired me to design the new Pittsburgh Whole Foods Market. He worked with developer, Steve Mosites, to incorporate a bunch of existing old warehouses into the project. The only new design was a small metal panel clad entrance piece. Steve told me later that it would have probably been cheaper to tear down the old buildings but that he was glad he hadn’t.

That’s when these other arguments become important: Restoring old buildings and adapting them to new uses undoubtedly improves the quality of users’ experiences. Clever developers and the City administration both now recognize this fact. How different this is from the 1960’s when the Civic Arena, Allegheny Center, and Penn Circle were built at tremendous cost to Pittsburgh’s history!

Low prices not only affect the amount of new construction that happens in the city, it effects the characteristics of this construction. In LA and Boston, I worked for others on various projects I would describe as “top-down” design. What do I mean by that? If a “bottom-up” design can be considered to be one where conventional construction systems are combined with one another sometimes to produced interesting and unexpected results, a top down design would be one where the architect and his engineers get to make up the parts. Most of the super-cool designs you see published in shiny architecture magazines are top-down design. Almost all new Pittsburgh construction is bottom-up because, again, owners’ profit margins are relatively low.

And new construction will likely continue to be bottom-up because 1) neither Pittsburgh architects nor developers feel empowered to take real risks and 2) Pittsburgh contractors for the most part are not well able to build out-of-the-box designs on a budget. On the one hand, this restricts the architects ability to create truly groundbreaking work. On the other, it assures a certain consistency in the new built environment, because we tend to see the same motifs and techniques repeated over and over.

This could well change if we get the Amazon expansion project, with its 50,000 predicted new jobs, but that’s another story… (2019 update: The winners were ultimately Northern Virginia and New York City…)

3) Fighting Banality

Working against the tendency for things to stay the same is the following fact: We’ve experienced a strong recovery from the collapse of the Pittsburgh steel industry and the 2008 housing bubble pop: Improving economic conditions, coupled with continued price appreciation, are providing stability for the housing market. Last year in Cranberry, for example, more than 200 new residential units were built at a cost of $45 million; in 2009, the corresponding construction spend was just $25 million.

Why is our recovery doing well? Well sure you can make the argument that our hospitals and universities are spurring a tech boom here in town that is creating jobs. But none of that would have happened unless Pittsburgh – let’s just say it – wasn’t a great place to live and work. In 2015, Pittsburgh was listed among the “eleven most livable cities in the world”; The Economist’s Global Livability Ranking placed Pittsburgh as the first- or second-most livable city in the United States in 2005, 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2014.7.

New Blood:

In the future young people will be more likely to stay in the city, and skilled people from other cities will continue to be attracted here. Facts prove this: The region gained younger people with college degrees faster than most areas. The number of college-educated residents age 25 to 34 went up by 33,371, nearly 34 percent, from 2000-13. So we are now experiencing a “brain gain” rather than “brain drain.”8

Living Arrangements:

These new residents have begun to change Pittsburgh’s household living arrangements: For example, household sizes are decreasing. In 2000, the average household size was 2.8 residents; by 2010, it was 1.89. Result: A surge in apartment buildings and in townhomes. Conversion of existing single family homes into apartments.

Predictions

Employment: In the long term real estate prices will continue to increase and Pittsburgh architects will continue to churn out their designs. Those of us in the construction industry will continue to have work.

Progressive Demand: The second more interesting result, at least for me, is that newcomers will demand a forward thinking architecture that will match their world-view. Pittsburghers who see themselves as world citizens will see images on the internet and on TV of buildings around the world and will identify with those buildings. And young people who arrive from other places will bring their tastes with them.

The task for Pittsburgh architects in the long term will be to design certain buildings that 1) speak to Pittsburgh yet 2) connect to buildings being built around the world. That is what I’ve been trying to do since I started my practice here in Pittsburgh.

1) Will Our New Buildings be Boring?

Earlier I said “certain buildings” would speak to Pittsburgh and the world. It is the nature of architecture and of development that most new projects will be mediocre. Architects live in difficult times. Why is this? I don’t subscribe to the notion adopted by Martin Heideger and countless other modern thinkers that our current times encourage thoughtlessness. My belief is that ALL times in our history have encouraged thoughtlessness. I mean how thoughtful can you be if you are only living on average till forty if you survive childbirth10. Humans are living better and longer now than at any other time in our history.

Nor I will can our boring buildings be blamed on our commodified culture, architects’ low fees, a loss of connection with the construction process, or a loss of connection among architects in our profession.

Here is what I think is going on:

A) Loss of Craft: The default buildings architects designed as recently as the 1930’s at least had a certain style and level of detail that is not possible today. One good example I noticed recently is the Coronado Apartments at the corner of Aiken and Centre. This building was constructed in 1935. It’s nothing so special – this isn’t world class design – but it’s just good, especially when you consider the subtle variation of the massing and the obvious care taken with the proportions. But labor prices have gone through the roof, making this level of detail unlikely today. Today’s construction techniques can not accommodate the old ways. Plasterers and stone masons are aging out of the work force.

B) No Rules: And designers no longer have the classical orders with their built-in goal of “firmness, utility, and delight” to use as a template; so today’s default designs are utterly generic. I am not optimistic that this will change. The norm will be that building designs will only be OK at best. But I cannot dwell on this loss, although it is one for sure. Instead let’s talk about how these “certain buildings” that aspire to more can obtain the qualities that allow them to speak to both Pittsburgh and the world?

2) Will Our Buildings Speak to the World?

How can a building speak to the world?

A) New Materials and Techniques: New materials and construction techniques are being introduced every day. In particular, computer templated CNC cutting and laser-cut shapes are changing the looks of new buildings around the world. I’m using gabions to form walls on one of my projects at the moment, I recently used a snap-cap for a Kawneer storefront system as a rainscreen. Architects are now building homes out of hay bales and insulated concrete forms. And then there are unexpected new materials like programmable cement, cross-laminated timber, power generating textiles, and building integrated bio-reactors11

B) The Computer: Architects around the world are using computers more and more. They have revolutionized the way we run our businesses.

In particular BIM (building information management) has changed the way we compile our designs and communicate with contractors. For large Pittsburgh projects Revit has become ubiquitous. And we can process huge amounts of data in the office as never before. Twenty-five years ago I would have employed an account, a secretary, and three draftsmen to do the work I can now do myself.

Secondly, visualization and rendering software has changed the way we design. In the past an architect would create one or two hand-drawn perspective drawings of a project to represent his formal intent. Now architects can now see our projects on the computer screen at full scale before they see them built. I use Rhino in the office combined with a plugin called Vray for my work and it has really increased my design skills. My buildings now possess a plastic quality they never had before. I can push and pull the building mass to achieve effects. I can model the way light will fall on the building, and I can instantly see the way the materials and colors relate to one another.

C) Sustainability: When I started thinking about sustainability I had no idea about building systems, I simply wanted to design buildings that connected back to nature. I was in love with plants and with natural materials. But as I learned more, I came to appreciate that much of what makes today’s new environmentally responsive buildings great is the stuff you can’t see. It’s the stuff under the hood, the insulation, the lighting systems, the plumbing fixtures, graywater systems, and the use of locally sourced materials.

Builders and designers can now create buildings that consume minimum energy without simply resorting to plastering roofs with photovoltaic panels. Now more than ever before, building owners and designers are dwelling on the long term benefits of green technology, especially in long-lasting commercial buildings. For a building that will last a hundred years or more, a fifteen-year-payback for green tech is a “no-brainer”. And as Larry Scarpa once told me, “low-income households need this the most. They have highest percentage of their income going to utilities… This is not heroic. It is common sense!”12

D) Form Follow Feeling: People around the world have similar emotional needs. Architects around the world have noted the banality of our contemporary urban infrastructure and are for the first making efforts to address the issue by “shaping emotional infrastructure” by designing experientially rich buildings that attempt to respond more directly to people’s needs and desires.

Experiential Buildings: Art has made a fundamental shift in the last one hundred years from being formal – object oriented – with the ideas baked in, to being user based, with the meaning of a work established by the sum of all user experiences. Architecture is the same. Young designers are now applying ideas from the fields of psychology, neurology, anthropology, and philosophy to their works like never before. They are thinking about how people feel within their buildings. This isn’t just touchy-feely hoo-ha. In the words of the USGBC, “design can be used to create places that support business objectives while at the same time being creative, elegant and innovative.” Indeed, experiential design “has value that has been understood and leveraged by some of the worlds most successful businesses.”13

Establishing Standards: New building standards like LEED, Living Building Challenge, and Passive House are facilitating the application of these new ideas. To be clear, ‘Beautiful’ and ‘sustainable’ do not have to be mutually exclusive concepts. The recently developed WELL Standard is of particular importance: According to their website, “WELL is the leading tool for advancing health and well-being in buildings globally.” WELL designers attempt to create a “flexible framework for improving health and human experience through design.”

Experiential Cities: As well, architects are also attempting to reenergize the way we experience the city. The 20th century produced many unfortunate urban designs as developers tore down whole portions of city's were torn down to make way for freeways, high-rises and, cheaply built, banal Modernist buildings. Because most new buildings resemble one another, many of our cities now look more alike than ever before, producing a sense of monotony and confusion in users.14 In Pittsburgh, folks like David Lewis and Ray Gindroz, and groups like PHLF have fought this tendency by advocating for the preservation of old buildings. As well they favor the creation of walkable neighborhoods containing a wide range of housing and job types.3) Will Our new Buildings Speak to Pittsburgh?

And how can a building speak to Pittsburgh? What inspires us? Is it:

The ever-present rivers with their yellow bridges, The ever-changing summer weather systems with their storms, The low gray winter clouds, The dense green of our summer foliage, The hills with their great walls, stairs, and inclines, Our people with their work ethic and down-to-earth warmth, Our excellent sport teams, Our parks and buildings, Our love of the Arts, and our steel heritage…

Or is it something else? Architects can respond to our green ecosystem with living roofs/walls and by creating views that connect a building’s interior to the outdoors. We can connect to our steel heritage with metal panels and exposed steel beams; make references to the heights, openings, massing, and material quality of adjacent buildings; create buildings that encourage communication between neighbors; and fill our buildings with art. Our buildings can become art!

Our Pittsburgh buildings can respond to the natural landscape. We can respond to our hills with roof shapes and changes in section. And now for the first time we can locate our new buildings in places that generate powerful experiences.

It used to be that you wouldn’t want to live on the top of a hill because it would be covered in smog, and you wouldn’t want to live by the river because it was likely to catch on fire. So you will find our city’s affordable housing projects on the tops of the hills and factories along the water. But as real estate folk know much better than I, those are no longer the highest and best uses in those places.

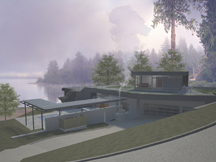

In the past year I have A) converted an old Aspinwall Marina into a visitor center, connecting the town for the first time in its history to the adjacent Allegheny River and B) Built a home on the Allegheny River for a Butler Street client who bought a river-adjacent property in a lower middle class neighborhood for practically nothing. You will see more and more projects like these in the future.

Conclusions

Pittsburgh’s visual landscape is changing and, although much of what will be built in the future will not be of interest, much will. In the last hour, we have talked about streams of global architectural design. I described contextualism, neomodernism, minimalism and neoexpressionism in architecture. Then we talked about trends in Pittsburgh design”. We discussed how Pittsburgh is affected by the world, we talked about building new versus renovating, and we discussed the building community’s fight against banality. Then I made a couple predictions: While many new buildings will continue to be boring, some will connect to designs being created around the world by means of new techniques and materials, the computer, sustainability, and wellness. And finally we discussed how our new buildings can speak to Pittsburgh.