[mk_fancy_title strip_tags=”” tag_name=”h3″ style=”” force_font_size=”” line_height=”” letter_spacing=”” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” font_family=”Times New Roman, Times, serif” font_type=”safefont”]

Below is an edited version of my email conversation with Wall Street Journal writer, Kris Frieswick, as she was preparing her November 2018 article on cliffside homes, which you can read here.

Kris: Hi Eric – Just wanted to make sure you got this email and my other one about number of bed/ baths etc. in art glass house. I really need this back asap. Thanks…

And here is my response, with her questions and my answers:

Eric: Hi Kris! The owner first contacted me in May of 2006. The structural engineers were “Atlantic Engineering”. The engineer in charge was John Schneider. The project engineer was Chris Kim.

Kris: What percentage slope is the home on?

Eric: The slope before construction was about one to two, or a fifty percent slope where the house is located.

Kris: When was the project completed/ ready for occupancy?

Eric: I submitted the project for an award once the project was complete at the end of August in 2011 (We won American Institute of Architects awards that year at both a local and a state level) I believe the project was completed that summer.

Kris: What part of the project was considerably more expensive than if you had done this project on flat land?

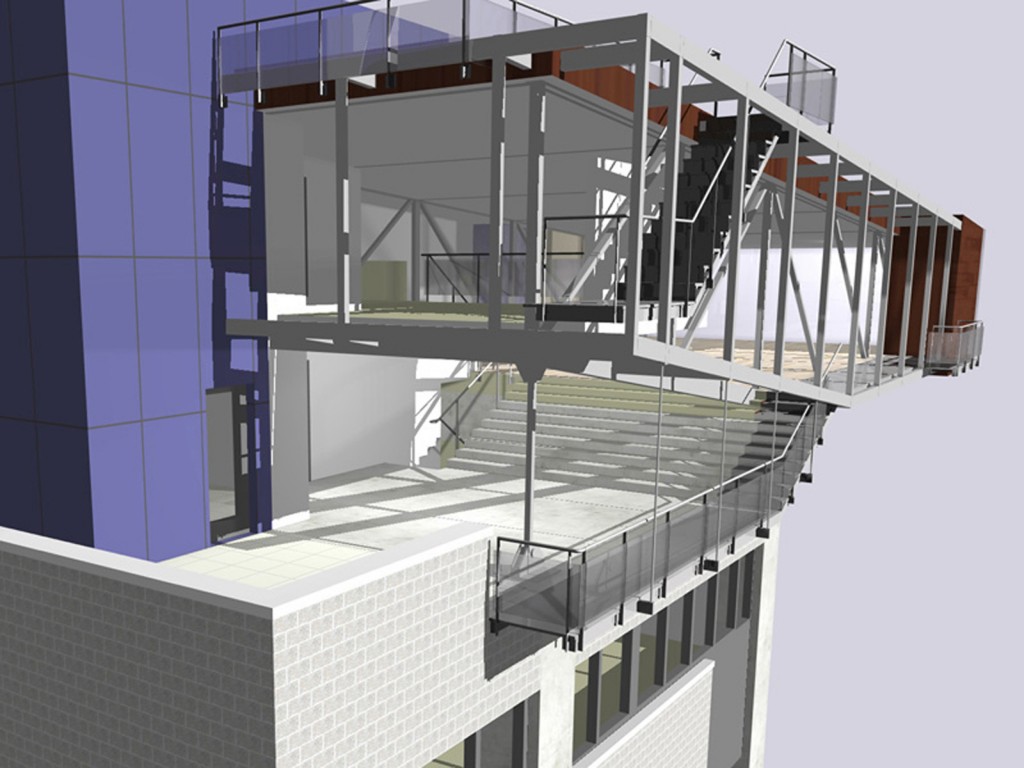

Eric: The foundations were considerably more extensive (and expensive) than they would have been on flat ground. The project is supported both by grade beams and by four huge caissons (concrete piers). Two of the caissons are seven foot in diameter while the two others are four foot six in diameter!!!

Kris: Which took the most time/ hassle from a permitting perspective?

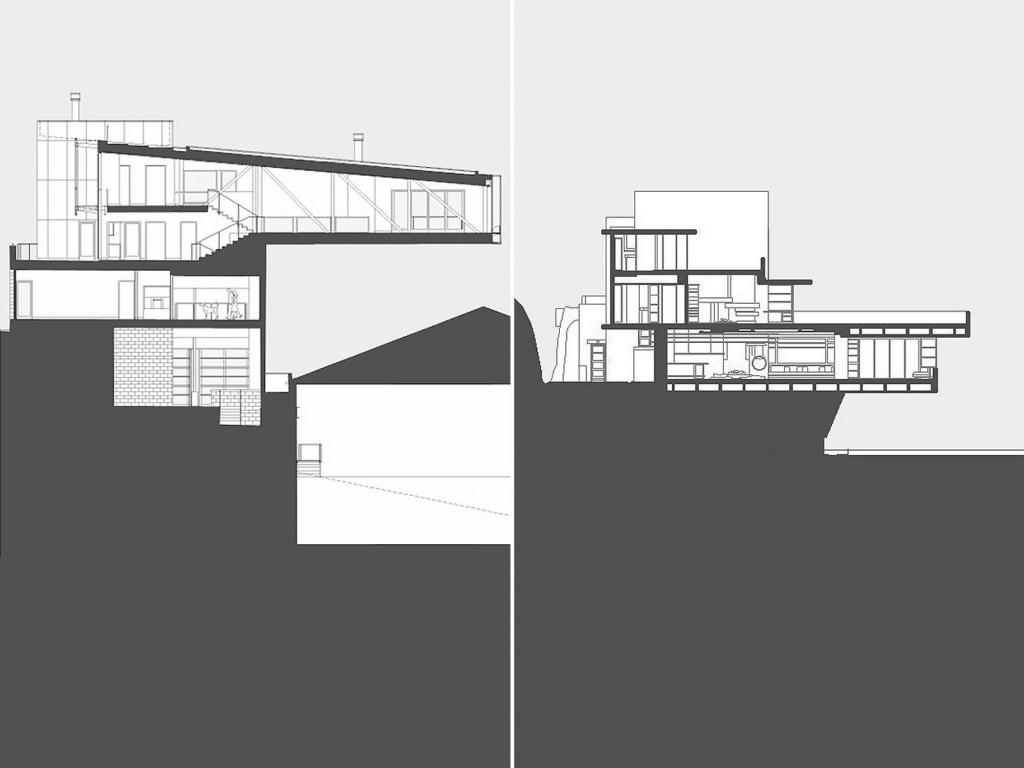

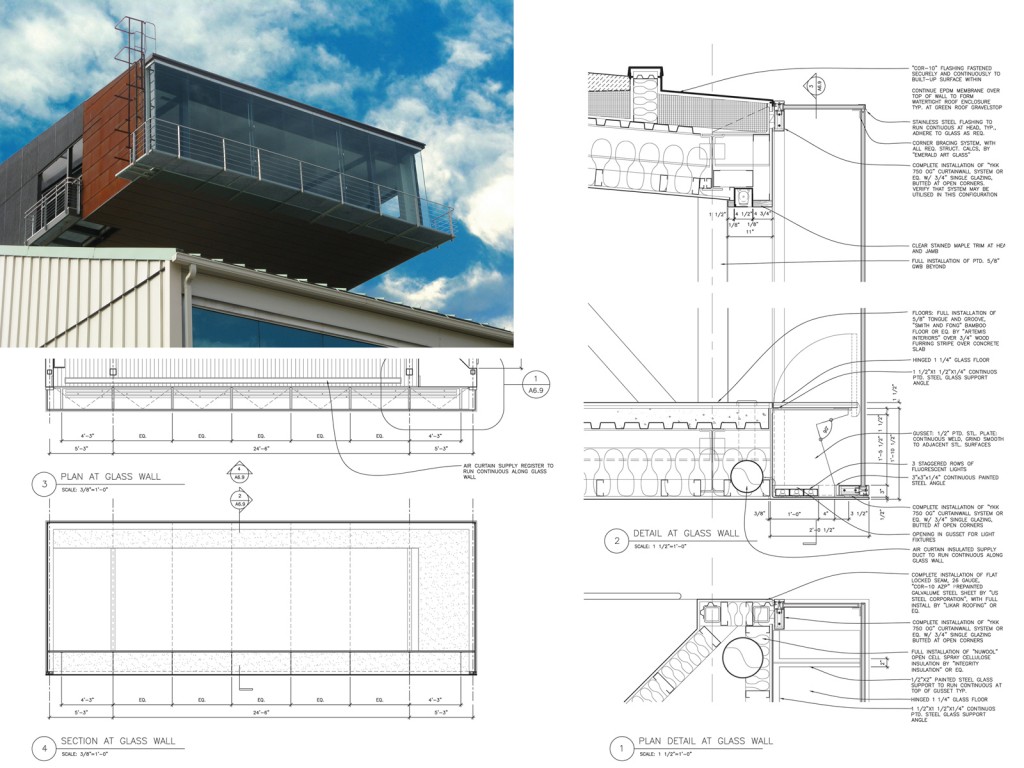

Eric: Our design intent was to cantilever the project over the glass factory below so the butted-glass front elevation would be located just above the highpoint of the warehouse gabled roof. That way the elevation would read from the street below like a giant glass billboard! Twelve foot of vertical fire separation was required between the two buildings. This determined the desired floor level of the cantilever. Now the permitted average building height in the project zone was forty foot, with that height calculated midway between the grade high-point and low-point. That number determined the final sloped roof elevation.

Getting the Zoning and Development Review Division folk from the Pittsburgh Department of City Planning to agree on our calculations took several meetings. It took a site visit by the Zoning Administrator himself to finally set things right. Then, once we finally had our zoning permission and ultimately submitted our over-the-top-complete construction document set for a building permit, we waited more than six months for approval, which we ultimately received without any comments or suggestions at all!

Kris: What was the biggest slope-related issue with this project?

Eric: The project is built like a see-saw with a 48 foot cantilever and a 28 foot backspan. As a result there are huge uplift forces in the back. It’s as though there is a large man sitting on one end of a see saw and you are on the other end standing on the ground trying to keep the man in the air by applying downward pressure. The closer you move to the fulcrum as you push down the tougher the job becomes. Amazingly, the entire job of keeping the project from tipping over is accomplished by 2, 3 inch diameter rods, each of which is designed to resist 125,000 pounds of force!!! These cables are in turn tied to a baseplate which is fastened into the caissons via a dense mesh of rebar. Then the caissons extend past the grade beams all the way down to bedrock, where they are firmly anchored. All this had to be constructed with almost inhuman levels of rigor and care in both summer and winter on a steep almost inaccessible slope!

Kris: How far down did you have to go to find bedrock and then how far into the bedrock did you put the piers for the house?

Eric: The distance to bedrock varies from grade between 14 and 28 feet. Each of the four caissons was drilled three feet into the bedrock!

Kris: What were the pertinent slope-related regulations you had to abide by, and what were the permits you had to get in order to complete the project?

Eric: There were no special slope related permits required. The project is located in an industrial zone in which a residential use is also permitted. We were not in a “hillside district”. As you know, Pittsburgh is a super-hilly city. Sometimes, as in our case, parts of properties have extreme slopes while other parts are almost flat and are considered usable.

Kris: How much did geo-technical studies of the parcel cost?

Eric: Geotech borings and review normally costs three or four thousand dollars here in Pittsburgh. Because 1) the project is located on a coal seam, 2) because the slope was substantial, and 3) because the site was difficult to access, the cost of these borings may well have been more than that!

Kris: What was the very first slope related permit/ challenge that you encountered with the site and how long did it take to resolve? In other words, what was the first thing that happened that gave the owners some inkling of what a pain in the butt the slope construction was going to be?

Eric: On my end as the architect, I knew enough about structures, having taught the subject at CMU for several years, to create a strong project diagram. Yet architects can draw anything. It’s getting the thing built that’s tough.

As Bob, the owner/contractor was thinking through how to build the project on this difficult site, he made the decision to actually buy a crane, rather than rent one, and to keep it on the site for the length of the project. That’s when it hit home for all of us what we were in for.

Here’s another story: I remember designing the entire cantilevered truss structure out of tube steel. Now tube steel has a really clean look with each piece welded cleanly to adjoining pieces. But when Bob tried to build the project using my details, he quickly discovered that his workers would have to balance on previously installed steel truss sections as they leaned out in space to weld each successive one into place. This would have been an exceedingly difficult (and dangerous) construction method. So we re-engineered the entire project out of wide flanges (big “I” shaped beams) that could be easily bolted one to another.

Hope all this helps. This was fun to think about again!

Kris quickly wrote me back:

Kris: Thank you Eric. This is incredibly interesting… I don’t think our readers will understand “caissons” so I’ll call them concrete piers in the story, if you don’t have a problem with that.

Then, after a series of interminable – I’m sure for Kris – additional emails that concerned themselves primarily with caissons and their nature, Kris said goodbye with the following note which left me feeling pretty good all in all:

Kris: Thank you so much for this. Your attention to detail is delightful! (really)

[/mk_fancy_title]